The North Market Historic District: A Saga of Transformation and Tenacity

Nestled in the heart of Columbus, Ohio, the North Market Historic District is more than a bustling food hall or a collection of historic buildings—it is a living chronicle of a city’s ambition, resilience, and reinvention. From its humble beginnings as a neglected cemetery to its emergence as a vibrant cultural and culinary hub, the North Market’s story weaves together architectural grandeur, economic booms and busts, and a community’s unwavering commitment to preserving its heritage. This narrative draws from historical accounts, blending the district’s pivotal moments, the vision of urban luminaries like Daniel Hudson Burnham, and the modern revitalization efforts that have restored its prominence, while delving deeper into the social, economic, and cultural forces that shaped its evolution.

The Roots of a City’s Heart (1813–1876)

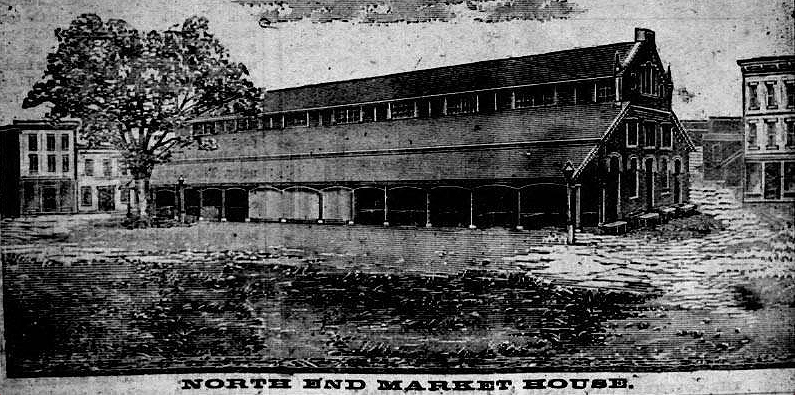

The North Market’s story begins in 1813, when the North Graveyard was established as Columbus’s first public cemetery, a quiet resting place for the city’s early settlers. By 1872, Columbus was no longer a frontier outpost but a growing hub of commerce and industry in the wake of the Civil War. The cemetery, neglected and overgrown, was cleared for development to accommodate the city’s expansion, though some remains were left behind, a fact that would resurface dramatically in later years. In 1876, a city ordinance established the North Market on this site, making it the second of four public markets in Columbus. Positioned just west of the Second Union Railroad Station, the market became a vital artery for farmers, merchants, and residents, offering fresh produce, meats, and goods in a bustling, open-air setting.

This period was marked by rapid growth, but also chaos. The Second Union Station, a critical transportation hub, brought thousands of visitors to Columbus daily, yet train traffic snarled High Street, delaying buggies, wagons, and pedestrians for up to seven hours a day. A tunnel built under the tracks for horse-drawn trolleys, intended to ease congestion, instead became a malodorous nuisance, underscoring the need for a more sophisticated urban plan. The North Market, while thriving, was part of a gritty, disorganized epicenter that reflected the city’s growing pains.

A Vision of Grandeur (1890s–1920s)

By the 1890s, Columbus was eager to shed its rough edges and establish itself as a city of wealth and sophistication. The city turned to Daniel Hudson Burnham, the era’s preeminent architect and urban planner, whose work defined the City Beautiful Movement—a philosophy that believed aesthetically pleasing cities could foster social harmony and civic pride. Fresh from his role as Director of Works for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where he crafted the iconic “White City,” Burnham was tasked with transforming the North Market area into a grand gateway rivaling the great market centers of Europe.

Burnham’s vision was transformative. In 1897, he unveiled the third Union Station, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece characterized by its monumental arches, ornate detailing, and classical symmetry. This was followed in 1899 by the High Street Arcade, a series of shops built atop a viaduct that finally resolved the traffic congestion caused by train crossings. The arcade, connected by an elevated roadway to another station miles away, mirrored the connectivity of modern airport trams. The Beaux-Arts style, with its grandeur and elegance, imbued the district with a sense of permanence and prestige, aligning with the City Beautiful Movement’s ideals.

The North Market District became Columbus’s glittering heart. Electric streetcars replaced horse-drawn trolleys, carrying 80 million passengers annually to destinations like The Ohio State University, Indianola Park, Minerva Park, and the city’s many opera houses and theaters. Lighted arches spanned High Street, earning Columbus the title of America’s “most brilliantly illuminated city.” Warehouses and wholesale markets flourished west of High Street, while the properties near Union Station became Ohio’s most valuable real estate.

At the district’s core stood 463 North High Street, home to the Parish Furniture and Rug Company. Completed in the early 20th century, this five-story showroom was a marvel of its time, boasting a two-story glass facade crafted from the largest sheets of glass then manufactured, a bronze elevator with a garden-frescoed ceiling, electric lighting, public restrooms, and exquisite woodwork. Shoppers arriving via luxurious Pullman train cars stepped through Union Station’s grand archways to behold this architectural gem, where they found treasures from around the globe: Prussian rugs, French chandeliers, Ottoman tapestries, Swiss clocks, and Italian leather goods. For those seeking more affordable options, nearby stores like Carlisle Furniture offered American-made furnishings from Michigan, Massachusetts, and Ohio.

This era of opulence was driven by Columbus’s economic dominance. The city led the world in manufacturing buggies, shoes, cigars, and farm tools, while Ohio’s agricultural sector thrived, producing more corn and wool than any other state. The years 1910–1914 marked a high point for farm prices, and with robust railroad connections to eastern ports, Ohio’s exports fueled an explosion of wealth. Grand mansions rose in streetcar suburbs and rural farmsteads, and their residents flocked to the North Market District to shop, dine on delicacies like Maine oysters, and stay in luxury hotels with private bathrooms, cementing the area’s status as a cultural and commercial beacon.

The Shadows of Decline (1940s–1970s)

The mid-20th century brought challenges that dimmed the district’s brilliance. The rise of the automobile shifted shopping to suburban malls, while declining farm prices and post-World War II manufacturing struggles weakened Columbus’s economic base. In 1948, tragedy struck when a fire, started by a 17-year-old arsonist, destroyed the original two-story brick North Market building. Merchants relocated to a war-surplus Quonset hut in 1949, a utilitarian structure that stood in stark contrast to the district’s former grandeur. The hut, located at the market’s original site, served as a temporary home for nearly five decades but struggled with declining foot traffic as supermarkets and suburban shopping centers gained dominance.

By the 1970s, the North Market District was a shadow of its former self. The last streetcar ran on September 5, 1948, as automobiles and neglected infrastructure ended the era of fixed-rail transit. Union Station’s passenger trains dwindled to one daily by 1970, then ceased entirely. The High Street Arcade, despite its 1974 listing on the National Register of Historic Places, was demolished in 1976 by a consortium led by the Battelle Memorial Institute. The Parish Furniture and Rug Company closed, and 463 North High stood abandoned, its once-dazzling facade boarded up.

Yet, amidst this decline, seeds of resilience took root. In 1965, Bob and Edith Holler transformed 463 North High into The Yankee Trader, a carnival supply warehouse that evolved into a beloved retail destination. Known for its Halloween costumes—ranging from Betty Boop to flying nuns—and party supplies, The Yankee Trader drew families for birthdays, bar mitzvahs, and graduations. Its annual Halloween rush became a local tradition, keeping the building alive as the district around it faded.

A Renaissance Fueled by Vision (1980s–Present)

The 1980s marked a turning point, as Columbus rallied to reclaim the North Market’s legacy. In 1982, the Columbus Landmarks Foundation secured the district’s designation as a National Register of Historic Places, laying the groundwork for preservation. Inspired by the successful rehabilitation of German Village, the North Market Development Authority (NMDA), formed in 1988, spearheaded efforts to restore the market’s role as a community cornerstone. In 1992, Nationwide Insurance sold a 1915 warehouse adjacent to the market’s original site for $1. After a $5 million renovation, the North Market relocated to 59 Spruce Street in November 1995, emerging as a modern food hall with over 30 vendors offering everything from artisanal cheeses to global cuisines.

The district’s revival extended beyond the market. In 1988, Columbus held a design competition for the Greater Columbus Convention Center, won by architect Peter Eisenman. Opened in 1993, the center’s innovative design drew on the area’s railroad heritage, with long, twisting forms evoking tracks and fiber-optic cables—a nod to Columbus’s transition from rail hub to information-age city. New businesses breathed life into the district: Barley’s Brewing Co. opened Ohio’s first brewpub since Prohibition in 1992 at 476 North High, while Martini’s introduced modern Italian dining at 445 North High. The Japanese Steak House relocated to 479 North High in 1990, adding to the area’s culinary diversity.

Preservation efforts also honored the district’s past. In 2000, the lone surviving arch from Union Station was re-erected in McPherson Park, a symbolic gesture of continuity. In 2004, a cap over Interstate 670, named Cap Union Station, echoed the original arcade’s design and function, reconnecting the district across the highway. Proposals for a future streetcar, with a stop at 463 North High, hint at a return to the area’s transit-driven roots.

The restoration of 463 North High became a cornerstone of the district’s renaissance. After The Yankee Trader closed in 2010 following Edith Holler’s death in 2000, the building faced potential demolition for a new hotel. Recognizing its historical significance, Yankee Brothers, LLC, led by Clyde Henry and Dave Price, purchased the property in 2011. Partnering with TRIAD Architects, a firm renowned for its preservation work, they meticulously restored the building to its Gilded Age splendor while infusing it with modern vitality. The upper floors now house elegant lofts with soaring ceilings, restored wood floors, and contemporary accents like stainless steel and granite. The ground floor welcomed Bareburger, a Brooklyn-based organic restaurant making its first foray outside New York, while the mezzanine features Denmark, a Euro-style bar offering craft cocktails and small plates. A wine shop and event space on the lower level cater to residents and visitors, and TRIAD Architects, inspired by the project, relocated their offices to the second floor.

A Legacy That Endures

The North Market Historic District continues to thrive, adapting to modern challenges while honoring its past. In 2020, the market expanded with a second location in Dublin, Ohio, demonstrating its enduring appeal. Despite disruptions from construction and the 2020 pandemic, the market remains a culinary and community landmark, drawing locals and tourists alike. In 2023, the discovery of North Graveyard remains during redevelopment added a poignant layer to the district’s story, prompting reflection on its earliest days and the lives that shaped it.

The North Market’s journey—from a 19th-century cemetery to a Gilded Age marvel, through decades of decline and a triumphant rebirth—mirrors Columbus’s own evolution. At its heart stands 463 North High, the district’s only building restored in accordance with National Park Guidelines, the Historic Resources Commission, and best practices of the American Restoration Council. This architectural gem, once a beacon of opulence and now a blend of history and innovation, embodies the district’s spirit. As plans for a new Hilton Hotel and potential streetcar line signal continued growth, the North Market Historic District remains a vibrant crossroads where Columbus’s past and future converge, inviting all to partake in its enduring saga.